Zinc and the Common Cold

- allygallop

- Sep 19, 2025

- 9 min read

Dietitians cannot help athletes avoid getting sick—risk of anything can never be zero. Yet our role is to help athletes reduce their risk of illness and, once sick, to minimize the duration and intensity of illness and days lost to training.

Zinc supplementation often comes up when teammates are sick and others are trying to ward it off, or when a player is sick and asks for pills. But what does the science say?

In this article, I want to review:

Zinc’s role in the common cold.

Daily intakes, at-risk populations, and dietary sources for zinc.

Interpreting what research studies exist for zinc supplementation and the common cold.

Zinc tablets versus zinc lozenges.

I’m going to focus this article on upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and its most frequent type of infection: the common cold. URTIs are “initially established in the mucosa of the nasopharynx before spreading to other regions, with local symptoms typically beginning in the throat before nasal congestion, [runny nose], sneezing and cough tend to develop.” (1)

What is Zinc’s Role in the Common Cold?

Although zinc has multiple roles throughout the body. I’m going to focus on immune health and the common cold—to which Nault et al. (2024) provided a nice summary for: (2)

“There are two main biologically plausible mechanisms for the potential effects of zinc on the common cold: 1) zinc may improve immune function (Maares 2016); and 2) zinc may interfere with the binding and replication of viruses involved in colds (Hulisz 2004; Read 2019). The mechanisms of zinc delivered by tablets, capsules, or syrups may differ from those of zinc delivered as lozenges (which are held and dissolved in the mouth, coating the tongue and throat) and those of zinc delivered as sprays or gels (which coat the nasal mucosa).”

Zinc plays a role in cell division, especially for rapidly-growing cells—like the immune system. Zinc is needed for the thymus, an organ located behind the sternum and in front of the heart, in producing specialized white blood cells called T cells (or T lymphocytes). (3)

Zinc also plays a role in barrier function, keeping the junctions between cells tightly connected to limit pathogen movement between and into them (like outfitting a suit of armour). (3)

Zinc: Daily Intake Recommendations, At-risk Populations, and Dietary Sources

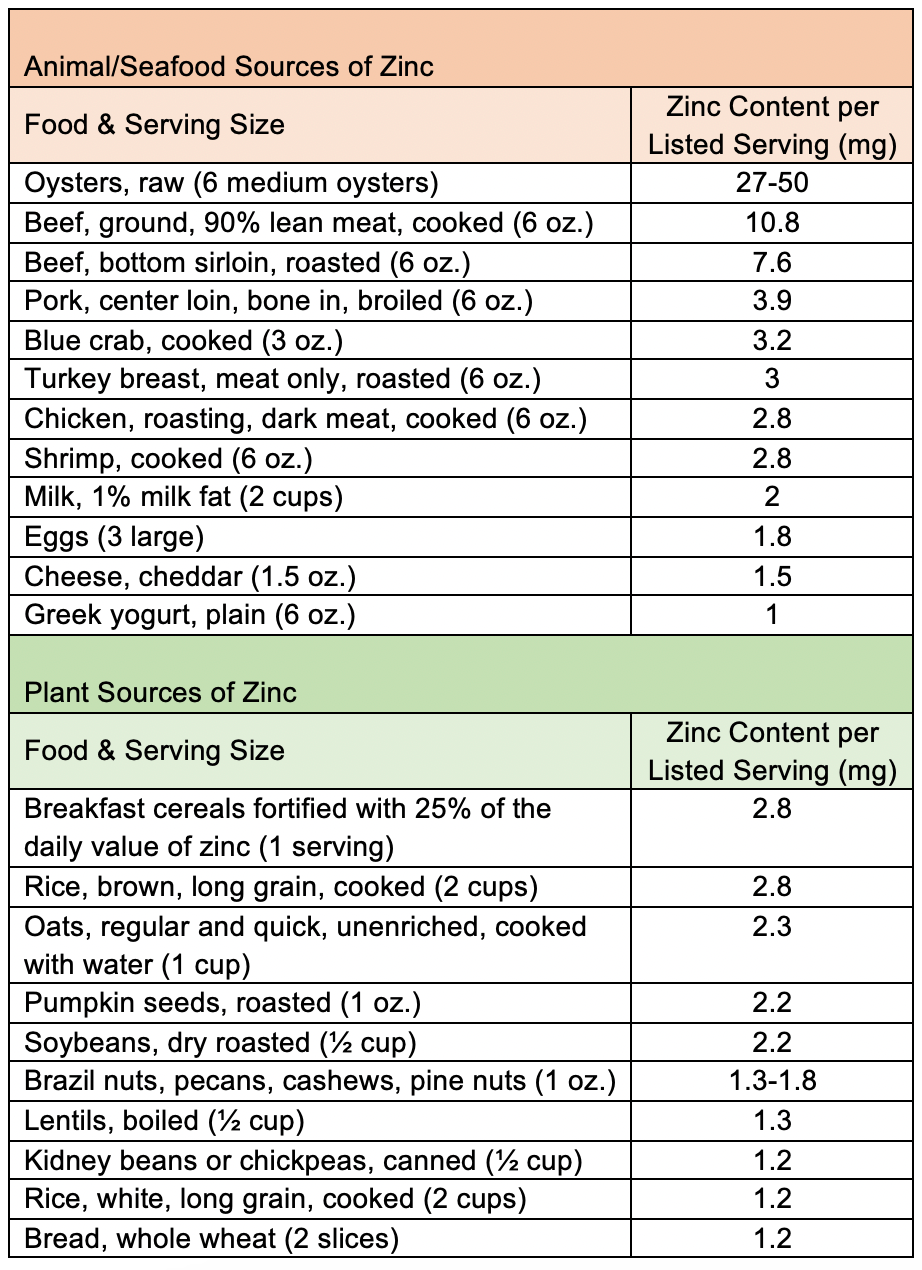

For adults aged 19 years and older, men require 11 mg zinc per day and women 8 mg (recommended dietary allowances, or RDA). For women, daily values increase during pregnancy and lactation. (4)

Zinc from plant sources is less readily available, due to the presence of phytates and fiber. These bind to zinc and form complexes that reduce absorption. For this reason, vegans and some vegetarians likely need intakes above the RDA and/or may benefit from a zinc-containing multivitamin or individual zinc supplement. (5)

However, zinc found in animal products is more bioavailable due to the lack of inhibitors and the presence of sulfur-containing amino acids that further boost zinc’s absorption. (5)

All values in the above table were pulled from the National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements and Oregon State University’s Linus Pauling Institute Micronutrient Information Center. Portion sizes have been adjusted to better reflect an athlete’s typical intake.

Given the above table, and especially for omnivores, individual zinc supplementation is unlikely warranted. And if supplementing, a zinc-containing multivitamin is plenty.

However, with increasing age (>50 years), other medical conditions affecting absorption, and/or a variable diet that may fluctuate animal- or seafood-rich sources of zinc, a zinc-containing multivitamin close to the RDA may be a safe bet.

Interpreting the Zinc Research

Research among the common cold, URTIs, and zinc supplementation in humans is a bit all over the place due to differences in measurements:

The form of zinc used (e.g., zinc gluconate, zinc citrate).

The delivery method (e.g., zinc lozenge, pill, liquid, nasal spray).

If illness prevention and/or treatment was the goal of the study.

If typical dietary intakes of zinc were established at baseline for study participants.

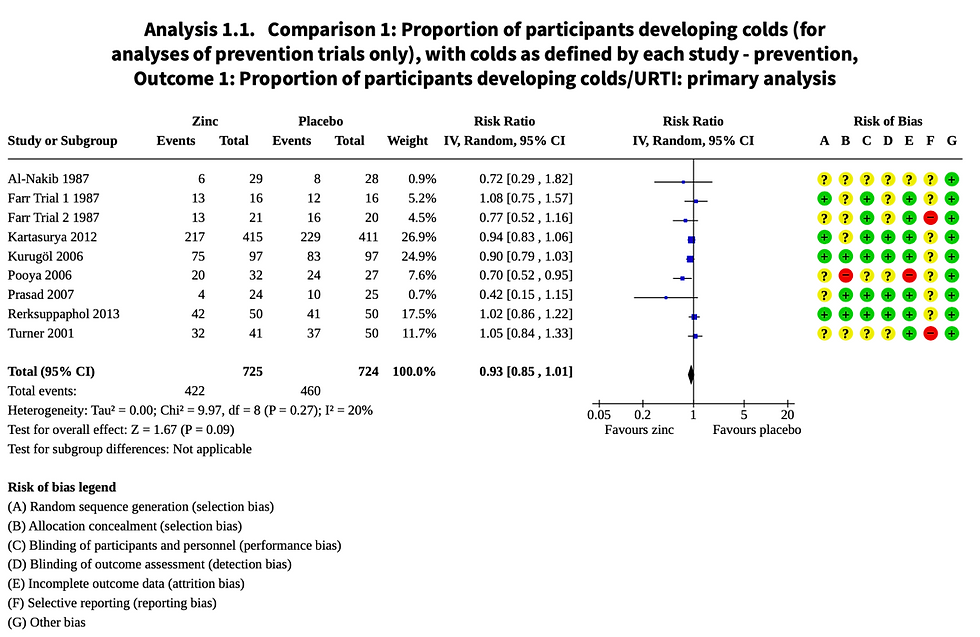

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews includes a review titled “Zinc for prevention and treatment of the common cold (Review)” published in 2024. (2) Of the 34 prevention or treatment studies it evaluated that included ~8,500 children and adults, researchers found the following when comparing zinc to a placebo:

Zinc for prevention: Little or no reduction in developing a cold, how many cold bouts someone would get over a certain period of time, days spent feeling sick, or severity of symptoms once sick.

Zinc for treatment: “There may be a reduction in the mean duration of the cold in days,” yet symptom severity may not differ between zinc and placebo groups. In adults, zinc supplementation may help reduce the duration of illness by two to three days. (2)

A very important caveat to the zinc-for-treatment studies was that dietary intake of zinc at baseline was not often established. So, was it the supplemental zinc in addition to a diet already meeting 100% of the RDA for zinc? Or, were the adults deficient in zinc and the supplementation increased their intake to the RDA? Oregon State University Professor Emily Ho, who studies zinc, voiced that zinc deficiency across the lifespan ranges from 12-15%, with risk increasing to 40-45% for those above the age of 55 years. (3)

Zinc Tablets and the Common Cold

What I wanted to further evaluate was what certified options sports dietitians have. Often, this means pills. Of the 34 studies included in the Cochrane Review, seven evaluated zinc tablets. One didn’t list the dose within their study and another didn’t list the type of zinc (but did include the dose). Of the six that did list doses:

All were prevention trials.

Outcomes measured included common cold and URTI prevalence.

The duration of the studies lasted 3-18 months.

The zinc forms included sulfate, gluconate, and bisglycinate.*

Zinc doses ranged from 5-45 mg/day.

Most researched infants or children, except for one categorizing young adults as those aged 18-54 years.

All included a placebo group.

Here’s what those six studies on pill supplementation showed regarding their varied impact on common cold prevention:

Mandlik et al. (2020): No difference between treatment and placebo groups for no or mild URTI or total infections. (6)

Somé et al. (2015): No difference in URTI risk between groups. (7)

Vakili et al. (2009): Statistically significant reductions in the risk of common cold, need for antibiotics, and days spent missing school due to sickness. (8)

McDonald et al. (2015): The zinc supplemented infants had a statistically significant lower risk of cold/acute URI. (9)

Rerksuppaphol & Rerksuppaphol (2013): No difference in risk of sickness, but the zinc supplemented group showed a shorter duration of runny nose, cough, and the likelihood of having two or more symptoms simultaneously. (10)

Prasad et al. (2007) – the only study in adults: Infection risk was significantly lower across those who supplemented with zinc (P<0.01), but when sub-analyzed for type of infection there was no statistically significant difference (e.g., likelihood of specifically becoming infected with a URTI, common cold, flu, or fever). (11)

*Brands are marketing zinc picolinate as being better absorbed by the body. However, “few data support this idea in humans … [and] limited work in animals suggest that increased intestinal absorption of zinc picolinate may be offset by increased elimination.” (5)

Zinc Lozenges and the Common Cold

Although the Cochrane Review noted the quality of the studies was very low, making it difficult to provide recommendations, Oregon State University’s Linus Pauling Institute makes the case for and recommends zinc lozenges or syrups, either in the acetate or gluconate forms*, for reducing the duration of common cold symptoms. (2,5) By slowly sucking on lozenges, zinc disperses from them and interacts with the tissues of the throat that are affected by the common cold (think of surfers and their white zinc sunblock that creates a physical barrier). (12)

The effective dose for lozenges seems to be at least 75 mg of elemental zinc per day, with treatment starting within the first 24 hours of symptom onset, and dosing continuing every 2-3 waking hours until symptoms subside. Although this dose is well beyond the 40 mg UL for zinc, research has supported daily doses as high as 180 mg via lozenges when sick that have not resulted in negative side effects. (4,5,12) Typical side effects of doses beyond 50 mg/day tend to be gastrointestinal related. (4)

If your organization allows Informed-Sport as a third-party supplement certifier, Healthspan Elite offers a zinc acetate lozenge (Zinc Defense Lozenges: 10 mg of which is ionic zinc). However, as of this September 2025 writing, NSF Certified for Sport lacks a lozenge (they do offer one zinc citrate chewable).

*Other forms of zinc have not been found efficacious.

In the Absence of a Certified Zinc Lozenge, What Can You Do as a Practitioner?

Your best bet would be to find a zinc chewable, either in the acetate or gluconate form, and slowly suck on one multiple times a day.

Otherwise, promote the dietary intake of zinc, supplement with a zinc-containing multivitamin ensure the athlete is at least meeting the zinc RDA, and promote other immune reinforcements, like vitamin C intake, sleep quality and quantity, minimizing alcohol intake, and optimizing caloric intake while addressing any common cold-related symptoms that may be affecting the athlete’s diet. For instance, the athlete has a sore throat and it hurts to consume harder or scratchier foods, or is suffering from congestion that may affect their smell, taste, or the desire to eat.

Key Takeaways

When healthy and eat like an omnivore: So long as you regularly consume animal products, a zinc-containing multivitamin is fine, if needed at all. Otherwise, you don’t need an individual zinc supplement. As noted above, zinc used as a preventive method to avoid the common cold doesn’t seem to be grounded in science.

When healthy and eat like a vegan or vegetarian: A zinc-containing multivitamin and/or an individual zinc supplement may be warranted.

If sick with the common cold: Zinc lozenges containing either zinc gluconate or zinc acetate may help reduce the duration of your sickness. Within the first 24 hours of symptom onset, suck on lozenges multiple times a day (every 2-3 waking hours) aiming for at least 75 mg zinc from those lozenges.

References

1) Davison, G., Schoeman, M., Chidley, C., Dulson, D.K., Schweighofer, P., … & Wilflingseder, D. (2025). ColdZyme® reduces viral load and upper respiratory tract infection duration and protects airway epithelia from infection with human rhinoviruses. J Physiol,603(6):1483-1501. http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40019230/

2) Nault, D., Machingo, T.A., Shipper, A.G., Antiporta, D.A., Hamel, C., … & Wieland, L.S. (2024). Zinc for prevention and treatment of the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev,5(5):CD014914 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38719213/

3) Lennon, D. (Host). (2025, June 3). #565: How zinc insufficiency impacts inflammation, immunity & again – Prof. Emily Ho. [Audio podcast episode). In Sigma nutrition radio. https://sigmanutrition.com/episode565/

4) National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. (2022, September 28). Zinc: fact sheet for health professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Zinc-HealthProfessional/

5) Higdon, J. (2001). Zinc. Linus Pauling Institute Micronutrient Information Center. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/minerals/zinc

6) Mandlik, R., Mughal, Z., Khadilkar, A., Chiplonkar, S., Ekbote, V., … & Khadilkar, V. (2020). Occurrence of infections in school children subsequent to supplementation with vitamin D-calcium or zinc: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutr Res Pract,14(2):117.

7) Somé, J.W., Abbeddou, S., Yakes Jimenez, E., Hess, S.Y., Ouédraogo, Z.P., … & Brown, K.H. (2015). Effect of zinc added to a daily small-quantity lipid-based nutrient supplement on diarrhoea, malaria, fever and respiratory infections in young children in rural Burkina Faso: a cluster-randomised trial. BMJ Open,5(9):e007828. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26362661/

8) Vakili, R., Vahedian, M., Khodaei, G., & Mahmoudi, M. (2009). Effects of zinc supplementation in occurrence and duration of common cold in school aged children during cold season: a double- blind placebo-controlled trial. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics,19(4):376-80.

9) McDonald, C.M., Manji, K.P., Kisenge, R., Aboud, S., Spiegelman, D., … & Duggan, C.P. (2015). Daily zinc but not multivitamin supplementation reduces diarrhea and upper respiratory infections in Tanzanian infants: a randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Nutr,145(9):2153-60.

10) Rerksuppaphol, S. & Rerksuppaphol, L. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of chelated zinc for prevention of the common cold in Thai school children. Paediatr Int Child Health,33(3):145-50.

11) Prasad, A.S., Beck, F.W.J., Bao, B., Fitzgerald, J.T., Snell, D.C., … & Cardozo, L.J. (2007). Zinc supplementation decreases incidence of infections in the elderly: effect of zinc on generation of cytokines and oxidative stress. Am J Clinl Nutr,85(3):837-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17344507/

12) Giana, A. (2016, March). Common cold. Linus Pauling Institute Micronutrient Information Center. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/health-disease/common-cold

13) Hemilä, H. (2017). Zinc lozenges and the common cold: a meta-analysis comparing zinc acetate and zinc gluconate, and the role of zinc dosage. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Open,8(5):1-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28515951/